Meditation for Athletes

The practice of meditation traces its roots back at least 5000 years to ancient Indian spiritual and religious traditions. In modern times there is increasing interest in meditation’s effects on physical and mental health, and performance. Many elite athletes attest to the power of meditation. In this article we will explore the benefits of meditation, the physiological mechanisms and provide practical applications.

In the Mindfulness-Acceptance-Commitment approach: the purpose of meditation is to change the way we respond to our thoughts, emotions and physical sensations.

Key principles involve:

-

Accepting how we feel instead of trying to avoid or change.

-

Understand that negative thoughts or feeling only hurt our performance if we let them.

-

Our thoughts are temporary and not reality.

This fits with the Biopsychosocial Model of Challenge and Threat, which suggests that perceiving stress as a challenge, instead of a threat, facilitated improved performance and task-relevant attention.

The benefits of meditation include:

-

Being in the moment.

-

Lack of distractions.

-

Acceptance of negative sensations or emotions.

-

Reduced feelings of stress, worry, social insecurity, fear and anger.

-

Increased serotonin levels. Serotonin is a hormone and chemical transmitter.

-

that regulates mood, sleep and digestion. Normal levels are associated with reduced anxiety and depression.

-

Increased dopamine levels. Dopamine is a hormone and chemical transmitter that is released during pleasurable experiences such as achieving goals and plays a key role in our motivation, mood, attention and learning.

-

Decreased perfectionism.

Performance

Atchley found that mindfulness techniques intended to promote self-awareness of the body during a 2km running test did not improve performance. This is not surprising considering that an external focus of attention, concentrating on the environment or goal, has consistently shown to be superior for performance than an internal focus, concentrating on the body or its movements. Applying maximum physical effort is often uncomfortable, so it would make more sense to focus on the goal, instead of how the legs and lungs are feeling! This shows that how and when we meditate is important.

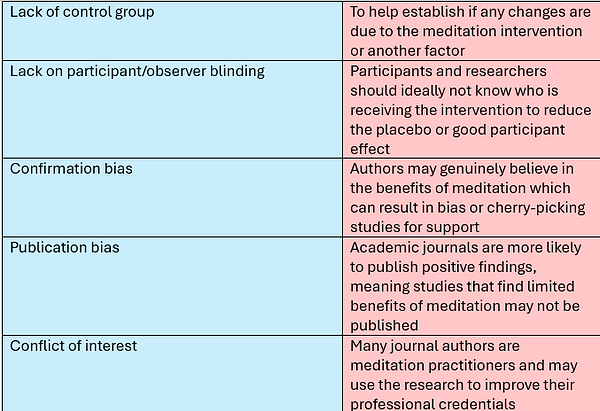

Meditation is associated with an enhanced ability to withstand pain. Experienced meditators were able to keep their hand immersed in ice cold water for over 45 minutes. This was associated with increased alpha wave activity, which are brain waves promoting relaxed, yet alert, states. It is unclear if this was due to extensive meditation practice, which has been shown to increase alpha waves, or if these types of individuals gravitate to meditation because their brains are already genetically predisposed for alpha wave activity. This study has several weaknesses with its methodology, which I have summarised in the table below. These are common with many studies on meditation and for that reason we may need to consider these and apply caution when interpreting their findings.

Research from over a quarter of a million people discovered that we are happier when our minds are focused on what we are doing in the present moment. Our minds tend to wander around half of the time and are we are less happy when we this happens, unless we are thinking about pleasant thoughts. Usually this happens unintentionally, preventing us from fully focusing on the task at hand and completing it to the best of our ability). Often this occurs without us realising as we are not self-aware of our own thoughts and experiences. We likely have a hierarchy of goals and mind wandering shifts our goal from the task at hand to our thoughts.

Neuroplasticity is the concept that our brains can adapt and change over time, depending on our thoughts and actions: when the neurons in our brain fire together, they wire together. Similar to how our body adapts to training, mindfulness meditation can be considered exercise for executive control. The more we practice, the better we can get.

Physiological Mechanisms

Meditation increases parasympathetic nervous system activity, often called the ‘rest and digest system’, and reduces sympathetic nervous system activity, or the ‘fight or flight’ response.

Parasympathetic Nervous System Features:

-

Feelings of relaxation.

-

heart rate, blood pressure, muscle nerve activity.

-

Improved digestion through release of digestive liquid and encourages movement of food down the digestive tract.

Sympathetic Nervous System Features:

-

Feelings of alertness

-

Increases heart rate, blood pressure, muscle nerve activation.

-

Increases blood flow to muscles and decreases to other organs (including digestive)

Stress is essential to stimulate adaptations. Hard training is necessary, which is often unpleasant and has some risk of injury. The Stress and Coping Model describes how our beliefs about potential threats or damage, and whether we are capable of handling these, play a major role in how our body responds to training and injury. Potential physiological mechanisms for this phenomenon include activation of the sympathetic nervous system, releasing adrenaline: preventing relaxation and diverting energy from other bodily functions such as digestion or immune system. Secondly, chronic cortisol stress hormone levels impair immunity, insulin response, memory and increase the risk of anxiety or depression. The effects of this are that we absorb less nutrients from our food for recovery, are more likely to get ill, insulin resistance will impair our ability to build and maintain muscle, and we can create a negative feedback loop where anxiety impairs recovery and performance, which then leads to further feelings of anxiety! While there remain many factors within our control, meditation and cultivating an attitude of mindful acceptance can be incredibly beneficial in handling the stresses and challenges athletes face. We can establish positive instead of negative feedback loops where athlete’s respond calmly and objectively to stress and setbacks, allowing them to handle these situations better, which then trains their mind and improves their self-belief to respond in the future.

This is supported by research that made participants perform a stressful test followed by either meditation or a general relaxation routine, while measuring cortisol and testosterone levels. They found that the meditation group ended with reduced cortisol hormone and greater testosterone levels, but this wasn’t because they experienced less stress from the test, because their hormone levels were similar immediately following the test. The difference was that the meditation allowed them to handle the stress better and bring their hormones to more favourable levels. This study also highlights the hormonal benefits of meditation including increased testosterone, growth hormone, oestrogen, insulin, and reduced cortisol. By contrast, some research has found some forms of meditation in fact increase the cortisol response to stress. However, this type of meditation, known as transcendental, focuses on ‘eliminating stressful experiences’ whereas mindful-acceptance meditation trains us to change our response to stress instead of trying to avoid it. This highlights that different forms of meditation result in different adaptations. The capability to handles stress and maintain hormonal balance can help athletes adapt to training.

There is evidence that meditation may improve sleep quality. There are numerous benefits of sleep including recovery, brain function, hypertrophy, fat loss, muscular endurance and injury risk. Sleep can be considered paying back the ‘sleep debt’ that we accumulate while awake. Time spent meditating may increasing this payback. This theory is supported by the evidence that people who meditate for long periods sleep less than those who perform shorter meditations. Some of the numerous proposed factors that improve sleep quality are listed below:

-

Increased Melatonin secretion in the pineal gland, promoting wakefulness in the morning and afternoon and encourages regular circadian rhythms.

-

Reduced Stress and parasympathetic activation, promoting relaxation.

-

Reduces sleep pressure through increased Theta & Alpha waves, this allows us to fall asleep more gradually and reduced the time we need to spend in non-REM sleep.

-

Greater payback of sleep debt during early sleep because of reduced sleep pressure. Meaning we sleep more efficiently.

-

Increased REM sleep due to requiring less non-REM sleep because meditation increases delta wave activity during deep sleep.

-

Practicing meditation increases gamma wave activity which may encourage late sleep to be more like meditation., The brain activity of alpha neurons during meditation has been described as like early sleep, although it should be noted that meditation differs from sleep because the individual remains alert.

A second potential mechanism may be that meditation counteracts the negative effects from insufficient sleep. Restricting sleep to five hours reduces alertness and reaction times, but meditation training reduced sleepiness and improved performance. This may be due to the practice of concentration increasing dopamine levels, which regulates blood flow to the areas of the brain associated with focus, namely the prefrontal and parietal association cortex.

Practical Recommendations

Despite the potential benefits, researchers report common obstacles to meditation including missing days, lack of commitment, lack of meditation leader and being too busy. To overcome these obstacles, we should remind ourselves of the positive effects of meditation that justify the investment of time and effort. There may be a perception that we need to spend time and money on travel and retreats to create the perfect conditions to meditation. However, even short periods of meditation can be beneficial, and mindfulness can be practiced anywhere, even while walking, driving or eating. It’s about being present wherever you are.

Easy forms of meditation include a few minutes of focussed attention meditation, focussing solely on each breath, or an external object such as a plant. If your mind wanders, bring it back. This is natural, so don’t react negatively when this happens. In fact, meditation can be considered refocussing practice, so the act of having to repeatedly bring your focus back is essential to the improvement process and changing your brain’s biochemistry. Always aim to be accepting and non-judgemental of yourself

I hope you have found this article interesting. This is the product of my study and experiences, but would not claim to be an expert on meditation. So I would recommend doing more study yourself or seeking out a meditation coach.

References

Anand, B. K., Chhina, G. S., & Singh, B. (1961). Some aspects of electroencephalographic studies in yogis. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 13, 452–456.

Atchley, A. R. (2011). An examination of the effects of mindfulness and task-relevant attentional focus on running performance (Master’s thesis, Western Kentucky University). Western Kentucky University. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1069

Baltzell, A., Caraballo, N., Chipman, K., & Hayden, L. (2014). A qualitative study of the mindfulness meditation training for sport: Division I female soccer players' experience. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 8(3), 221–244.

Basso, J. C., McHale, A., Ende, V., Oberlin, D. J., & Suzuki, W. A. (2019). Brief, daily meditation enhances attention, memory, mood, and emotional regulation in non-experienced meditators. Behavioural Brain Research, 356, 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2018.08.023

Blascovich, J., & Mendes, W. B. (2000). Challenge and threat appraisals: The role of affective cues. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Feeling and thinking: The role of affect in social cognition (pp. 59–82). Cambridge University Press.

Bull, H. G., Atack, A. C., North, J. S., & Murphy, C. P. (2023). The effect of attentional focus instructions on performance and technique in a complex open skill. European Journal of Sport Science, 23(10), 2049–2058. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2022.2150895

Burns, J. M. C. (2017). Getting to another level: Why basketball players use mindfulness meditation. The International Journal of Health, Wellness and Society, 6(4), 81–95.

Chatterjee, S., & Mondal, S. (2014). Effect of regular yogic training on growth hormone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate as an endocrine marker of aging. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014, Article 240581. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/240581

Fan, Y., Cui, Y., Tang, R., Sarkar, A., Mehta, P., & Tang, Y. Y. (2024). Salivary testosterone and cortisol response in acute stress modulated by seven sessions of mindfulness meditation in young males. Stress, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2024.2316041

Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2004). A mindfulness-acceptance-commitment-based approach to athletic performance enhancement: Theoretical considerations. Journal of Behavioral Therapy, 35, 707–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80016-9

Goleman, D., & Davidson, R. J. (2017). The science of meditation: How to change your brain, mind and body. Penguin Life.

Guerriero, L. E., & O’Hara, B. F. (2019). Meditation, sleep, and performance. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 4(2), Article 031. https://doi.org/10.21926/obm.icm.1902031

Guzzetti, J. R., & Banks, S. (2022). Dynamics of recovery sleep from chronic sleep restriction. Sleep Advances, 4(1), zpac044. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleepadvances/zpac044

Huang, K., & Ihm, J. (2021). Sleep and injury risk. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 20(6), 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0000000000000849

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40931861

Kohler, M., Rawlings, M., Kaeding, A., Banks, S., & Immink, M. A. (2017). Meditation is effective in reducing sleepiness and improving sustained attention following acute sleep restriction. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1(2), 210–218.

Koncz, A., Demetrovics, Z., & Takács, Z. K. (2020). Meditation interventions efficiently reduce cortisol levels of at-risk samples: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 15(1), 56–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2020.1760727

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer.

Lopes, T. R., Pereira, H. M., Bittencourt, L. R. A., & Silva, B. M. (2023). How much does sleep deprivation impair endurance performance? A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science, 23(7), 1279–1292. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2022.2155583

MacLean, C. R. K., Walton, K. G., Wenneberg, S. R., Levitsky, D. K., Mandarino, J. P., Waziri, R., Hillis, S. L., & Schneider, R. H. (1997). Effects of the transcendental meditation program on adaptive mechanisms: Changes in hormone levels and responses to stress after 4 months of practice. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 22(4), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(97)00003-6

Park, J., Lyles, R. H., & Bauer-Wu, S. (2014). Mindfulness meditation lowers muscle sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in African-American males with chronic kidney disease. American Journal of Physiology–Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00558.2013

Sinha, S. S., Jain, A. K., Tyagi, S., Gupta, S. K., & Mahajan, A. S. (2018). Effect of 6 months of meditation on blood sugar, glycosylated hemoglobin, and insulin levels in patients of coronary artery disease. International Journal of Yoga, 11(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_30_17

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2006). The restless mind. Psychological Bulletin, 132(6), 946–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946

Song, J., Park, S. J., Choi, S., et al. (2023). Effect of changes in sleeping behavior on skeletal muscle and fat mass: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 23, Article 1879. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16765-7

Sung, M. K., Lee, U. S., Ha, N. H., Koh, E., & Yang, H. J. (2020). A potential association of meditation with menopausal symptoms and blood chemistry in healthy women: A pilot cross-sectional study. Medicine, 99(36), e22048. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000022048